Should I Build Review Into Long Range Plan Teaching

Today'south guest post is written by Julie Stern, an author and consultant who focuses on conceptual understanding.

Have you ever been frustrated past how chop-chop students seem to forget what you've taught them? Or by their struggles to use what they've learned in one context in a new, but related context? When we intentionally help students build schema, we can solve both problems.

Schema is a mental structure to help us understand how things work. It has to do with how we organize knowledge. As we take in new information, we connect it to other things we know, believe, or have experienced. And those connections class a sort of structure in the brain.

Consider the following quotes from instruction researchers:

"The reason experts think more than is that what novices run into as separate pieces of data, experts run into as organized sets of ideas." Donovan & Bransford, 2005

"It turns out that people who do well in math are those that make connections and see math equally a connected subject." Jo Boaler, 2014

"Cognitive scientists remember of deep learning—or what you might call 'learning for understanding'—equally the ability to organize discrete pieces of cognition into a larger schema of agreement." Meta & Fine, 2019

If a hallmark of expertise is organized thinking, how do we help students to see the structure of the subject nosotros are educational activity?

Enter the noble index card. This low-tech tool has the ability to revolutionize your educational activity exercise. Mail service-it notes piece of work, too. They allow students to physically build and manipulate schema as they acquire. Allow me show you.

First, we start with individual concepts, which are the edifice blocks of schema. Concepts are words we use to organize and categorize our globe. When nosotros expect at our curriculum standards or learning outcomes, the nouns are unremarkably the concepts. Examples include: story patterns, grapheme, fraction, whole number, living things, organelle, leadership, and sovereignty.

Nosotros can showtime with examples of concepts that students already know. For instance, we tin use ocean, desert, and pelting woods equally examples of the concept of habitat. Or nosotros can put groups of different concepts in front of students and ask them to try to decide the features that differ between the groups. I middle school science teacher put a few simple circuits on 1 table and a few parallel circuits on some other tabular array. Students tinkered with the circuits on each tabular array and discussed what differences they noticed between the two groups.

Once students acquire initial understanding of a concept, it's time to consolidate their understanding (Fisher, Frey & Hattie, 2017). They tin practice this using index cards, collecting these cards as visual representations of the edifice blocks of expertise. Many teachers use the Meet-Information technology model. Encounter the steps in Effigy 1 below.

Effigy 1: See-Information technology Model for Consolidating Understanding of Single Concepts

Source: Adjusted from Stern et. al, 2017; originally adapted from Paul & Elder, 2013.

Social studies teacher Jeff Phillips asked his students to complete this activeness to consolidate their understanding of the concept of "services." And English language/linguistic communication arts teacher Trevor Aleo asked his students to complete the steps with the concept of "symbol." Run into both educatee examples in Figure 2 beneath.

Figure 2: SEE-IT Menu Examples for Social Studies and Language Arts

When students elaborate on their agreement of concepts, it presents an opportunity to correct any lingering misunderstandings. Encounter the student example in Figure three beneath. Notice that the pupil wrote that a leader has a "right" to change guild'south perspective, demonstrating a common defoliation in social studies. In a democratic society, governments accept dominance derived from the people, while people maintain rights, derived from birth. This is an important distinction that we tin at present correct.

Figure 3: Example of Misconception of a Concept

Now—on to the actually good stuff. Once students have acquired, corrected, and consolidated their understanding of private concepts, it's fourth dimension to connect the concepts in relationship. That's where schema is built.

This next step comes during and afterwards students have explored a fact-rich context such as a complex mathematical problem, science experiment, literary text, or social studies context. Students use their learning experiences to generalize into organizing principles well-nigh how the globe works (Erickson & Lanning, 2014). They can now physically conform the notation cards or Mail service-it notes to demonstrate how concepts are related. Then, they should write a sentence or paragraph that explains the human relationship.

Science teacher Julia Briggs asked her students to connect the concepts of matter, arrangements, subatomic particles, and properties. So, Ms. Briggs asked students to write a couple of sentences about how the concepts are related. Notice how the annotation cards serve to make a structure among the scientific discipline concepts in the example in Effigy four below.

Figure four: Science Example of Sorting and Connecting Concepts to Build Schema

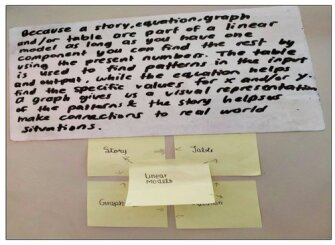

Similarly, math teacher Courtney Paull asked her students to connect five concepts using Mail-it notes: linear models, table, story, graph, and equation. Then, they wrote a paragraph nearly how the concepts are related.

The students wrote,

Because a story, equation, graph and/or table are part of a linear model, as long as you have ane component you lot can discover the rest by using the present numbers. The tabular array is used to observe patterns in the input and output, while the equation helps find the specific values for x and/or y. A graph gives us a visual representation of the pattern and the story helps us make connections to real world situations."

Wow. Imagine if we had all learned mathematics this way. See the flick in Figure 5 beneath.

Effigy 5: Mathematics Case of Sorting and Connecting Concepts to Build Schema

The index cards and Post-it notes help students to physically build an organizational structure or schema direct on their desks. Importantly, schema is non built with just one pass at making connections. Schema is built through multiple experiences of making connections. This activeness can and should be repeated throughout the unit, semester, and school year. Students can add more concepts and make more than connections each time they transfer their agreement to a new state of affairs, somewhen writing several paragraphs virtually how the concepts are connected and related.

Regular readers of this blog are likely familiar with John Hattie's research, called Visible Learning. His meta-analysis of factors that influence student learning shows that an effect size of .40 is the average of all influences. So, we can call up of .40 roughly as a twelvemonth's worth of growth. Annihilation in a higher place .40 has the potential to accelerate pupil accomplishment (Visible Learning Plus, 2019).

Here's how the strategies above measure up:

- Using examples of concepts from students' prior knowledge = .93

- Clarifying misconceptions about concepts (conceptual change) = .99

- Asking students to elaborate and organize their understanding of concepts = .75

- Mapping concepts in connection to other concepts = .64

- Strategies to transfer learning = .86

Heady, isn't it? Intentionally teaching for schema is supported by both cognitive science and meta-analysis of educatee achievement. Grab some alphabetize cards or Mail service-it notes and help your students both retain data and transfer it to new situations.

For more practical ways to apply this inquiry in the classroom, encounter or Tools for Didactics Conceptual Agreement, Secondary or Tools for Teaching Conceptual Understanding, Elementary .

Opening image courtesy of Getty Images.

References:

Boaler, J. (2014). Bout of Mathematical Connections. YouCubed, Stanford Graduate Schoolhouse of Pedagogy. Retrieved from: https://www.youcubed.org/resources/bout-mathematical-connections/

Donovan, S., & Bransford, J. (2005). How students acquire: History, mathematics, and science in the classroom. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Erickson, H. L., & Lanning, L. A. (2014). Transitioning to concept-based curriculum and education: How to bring content and process together. Thou Oaks, CA: Corwin Printing.

Fisher, D., Frey, N., & Hattie, J. (2017). Visible learning for literacy, grades Grand-12: Implementing the practices that piece of work best to advance student learning.

Meta, J. & Fine, S. (2019). In search of deeper learning. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Paul, R. & Elder, L. (2013). How to write a paragraph: The art of noun writing (tertiary ed.). Tomales, CA: Foundation for Critical Thinking.

Stern, J., Ferraro, K., & Mohnkern, J. (2017). Tools for instruction conceptual agreement, secondary. Grand Oaks, CA: Corwin, A SAGE Visitor.

Visible Learning Plus. (June, 2019). 250+ Influences on Pupil Achievement. Corwin Printing: One thousand Oaks, CA. Retrieved from: https://us.corwin.com/sites/default/files/250_influences_chart_june_2019.pdf

The opinions expressed in Peter DeWitt's Finding Common Ground are strictly those of the author(due south) and do not reverberate the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Instruction, or any of its publications.

Source: https://www.edweek.org/education/opinion-what-is-schema-how-do-we-help-students-build-it/2019/10

0 Response to "Should I Build Review Into Long Range Plan Teaching"

Post a Comment